Robert-Jan Korteland makes educational innovation visible

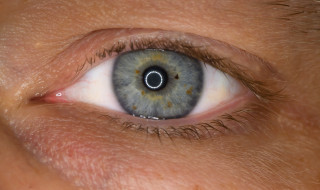

Ever since his early years in education, Robert-Jan Korteland has been putting his fascination with didactics into practice. With a background in optics and optometry, he wondered during his studies in educational sciences: “Can a teacher teach better if they can see in real time what a student is looking at?”

Robert-Jan Korteland

We are in the Digital Education Lab of the teacher training programs at Utrecht University of Applied Sciences. Everywhere we look, we see devices that invite experimentation: laser printers, wood carving machines, a card punching press, 3D printers, and a sturdy flight case. Inside, we hear, is the EyeLab: a mobile research station full of cameras and eye-tracking equipment.

For Robert-Jan Korteland (43), lecturer-researcher and coordinator of the Digital Innovation for Education (DIO) program within the Meaningful Digital Innovation research group, it feels like coming home here. It is the place where education, curiosity, and technology intersect. “A student has developed software that allows me to use eye-tracking glasses to see what two people are looking at simultaneously while they are learning,” he explains enthusiastically. “This allows me to operationalise the shared visual attention of, for example, a teacher and a student. So I can literally measure how far apart two gazes are during a learning process.”

“I like to calculate things, to examine them accurately. Always with the thought in mind: what will this mean for students and teachers in real learning situations?”

This explanation is typical of Korteland. He likes to make something that may sound vague or theoretical to others concrete and measurable. Or, as he puts it himself: “I like to calculate things, to examine them accurately. Always with the thought: what will this mean for students and teachers in real learning situations?”

Grateful work

Robert-Jan Korteland does not see a straight career path, but he does see a consistent motivation. For him, it's about meaningfully engaging with the human capacity to learn, see, and understand. As a child, he loved to draw eyes. “Eyes work like magnets,” he says. “Objects that resemble a face attract attention. It's the reason why babies like to crawl toward electrical outlets. Eyes have always been a source of inspiration for me.”

After school years in which Korteland preferred to spend his time skateboarding and playing guitar, he studied nursing, optics, part-time optometry, a master's degree in educational sciences, and development work in Ukraine and West Africa. During a mission in Lviv, he noticed how essential and vulnerable access to eye care is. “I fitted glasses for orphans and homeless people there and also did eye tests in prisons. Making a meaningful contribution through your profession without expecting anything in return was very rewarding work for me. It pains me to see that most of the buildings in Ukraine from that time are no longer standing and that many lives have been lost.”

"Eyes have always been a source of inspiration for me"

Button science

Korteland has now been working on a PhD at Utrecht University for a year and a half. His research focuses on ‘cognitive apprenticeship teaching in (para)medical education’, the master-apprentice model in which learning takes place by working closely with the expert.

"That goes all the way back to the old days. We've been doing it that way for centuries. A shoemaker who passed on his knowledge one-on-one to his son in the workplace was the norm. I am trying to refine this master-apprentice concept with my PhD, because nowadays there is a lot of technology to be learned in the medical field. You have to be able to operate many types of equipment when performing eye examinations. ‘Button science’ is also part of medical knowledge that can be transferred in this way."

This is where ‘his’ EyeLab comes into the picture. With the dual eye-tracking setup, Korteland measures how experts and beginners divide their visual attention during the reading process. “What happens when the teacher explains an anatomical structure? Do the student's eyes move to the same point as the teacher is looking at? And how quickly does that happen? These are interesting topics to investigate.”

“You have to be able to operate many types of equipment when performing eye examinations.”

Honest Mirror

Korteland divides his valuable time between two locations at Utrecht Science Park. "Utrecht University of Applied Sciences, my home base, is more practice-oriented. Universities provide a wealth of knowledge that we use to facilitate evidence-based or evidence-informed education in practice. I investigate whether a particular teaching method is effective. I publish my findings and try to valorise them in education. Here at the University of Applied Sciences, you can simply create a product or innovation based on what we have learned through scientific research. I find that a wonderful and appealing prospect."

The line of research that Korteland coordinates at HU falls under the Meaningful Digital Innovation research group. "Within the research group, we are working on Honest Mirror, among other things. This is an AI-supported application that allows you to develop presentation skills. The tool recognises posture and gestures and then provides feedback on the presentation. We are investigating the effectiveness and impact of that feedback on the development of presentation skills.“

“Here at the university, you can simply create a product or innovation based on what we have learned through scientific research.”

Korteland adds: ”We are also investigating themes such as digital inclusion for end users. That really makes my heart beat faster. Especially when you see how it works and what we can achieve with it. And how much fun the accompanying workshops are. Through the Publinova platform facilitated by SURF, we are now setting up an environment where we can store all that knowledge and resources according to open science principles. We are about to release the software, which is quite exciting."

A step back

According to Robert-Jan Korteland, meaningful digital innovation does not stop there. Together with committed students and teachers, he also looks at the ethical side of digitisation. “What actually happens to the data? And how inclusive is the software? There are students here who, for example, have only one arm or can only give a presentation while seated. That's why Honest Mirror offers the option of not receiving feedback on hand gestures, for example. Or you can click on the ‘dyslexia’ icon, which changes the way the feedback is formulated and the font used.”

“We are working on technology to improve learning environments and skills. But we want to test and understand that technology first, to see what effect it has on people.”

Peer reviews on innovation

“We all have personal values and standards,” Korteland continues. "But we also live in a diverse society where digitisation is almost impossible to keep up with. In that process of digitisation, we sometimes take a step back from the research group. We call this Value Sensitive Design (VSD). From the start of a design or innovation process, you engage in peer review discussions with various stakeholders or future end users about the advantages and disadvantages of innovation.“

He adds, ”We are working on technology to improve learning environments and skills. But we want to test and understand that technology first, to see what effect it has on people. I recently saw the film Oppenheimer. It immediately made me think of VSD. When atomic power was discovered, no one knew what disastrous consequences it would have. If we come up with and develop something today, it could have far-reaching consequences tomorrow. We'd better think about that in good time."

“We live in a diverse society in which digitisation is almost impossible to keep up with”

The korfball club

Although he does a lot of research and innovation, Korteland remains first and foremost a teacher. This is evident from the nominations he has received several times for HU Teacher of the Year. "I genuinely make time for students. They find me straightforward, but they appreciate the attention I give them. I believe that both teachers and students should work hard. You have to be able to rely on each other and not forget to have fun. Then you'll get there together. I call that ‘work hard, play hard’. With a wink, he adds: “You can laugh with me, but if a student messes up, I can also fail them with a smile.”

“In our profession, we make choices all day long. For me, however, the most important thing is that teaching with the help of technology should never exclude people. Didactics is not a trick. It's all about personal interaction. You can guide and supervise that, but I'm seeing more and more that students are picking this up very well among themselves. Even with technology.”

Finally, Kortland says: “Students share good practices, give each other tips on how to study smart and complete assignments efficiently and to a high standard. Digitalisation offers fantastic ways to assess assignments and tests properly and monitor students' personal and academic development. I find that an attractive dynamic. Education is increasingly becoming something you do together.”

Balancing research, teaching, and a family with four young children also requires discipline. His wife works in primary education, and together they run a household that thrives on rhythm, attention, and commitment. “You have to organise your schedule well. Sometimes you submit a manuscript at 1 minute before midnight, sometimes you just have to be at the korfball club on time. It's all part of the job. Every day is different. That variety gives me energy.”

Text: Edwin Ammerlaan

Photos: Jelmer de Haas

Robert-Jan Korteland

Robert-Jan Korteland is coordinator of the Digital Innovation for Education (DIO) program line within the Meaningful Digital Innovation (BDI) research group at Utrecht University of Applied Sciences. As a lecturer-researcher, he is affiliated with the teacher training programs at the Archimedes Institute. He is also a PhD candidate in the Department of Education and Pedagogy at Utrecht University.

He previously worked as a college lecturer and educationalist in the optometry and orthoptics programs at the Institute for Paramedical Studies. During his PhD, he is researching how teacher-student (master-apprentice) interactions during the (learning to) perform complex professional tasks in the medical domain can best be designed to promote the development of expertise.